Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition Paper Explained (Resnet paper)

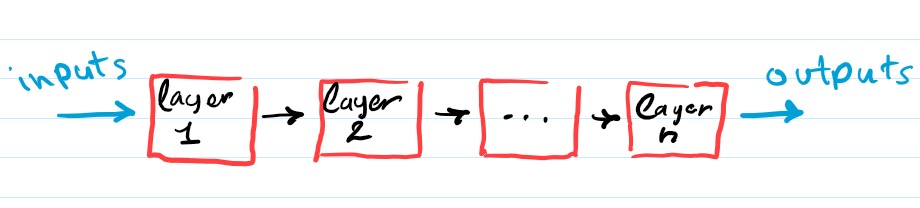

A neural network can be viewed as a number of layers stacked on top of (or next to, look at it however you want) each other, where the output of some layer, is input to the layer next to it (at least simple neural networks can be viewed this way)

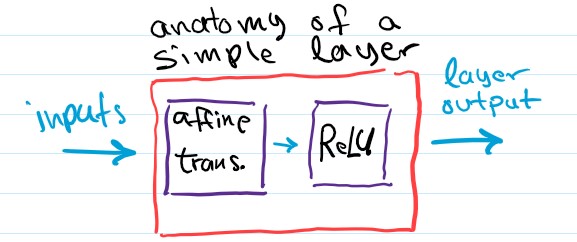

Normally, these layers are constructed using an affine transformation and a non-linear function like ReLU or tanh.

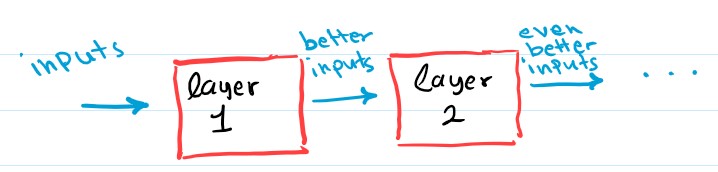

These layers can be also viewed as “feature extractors”, a layer receives its inputs from its previous layer’s output and tries to find a better view, a better way to represent these inputs/features.

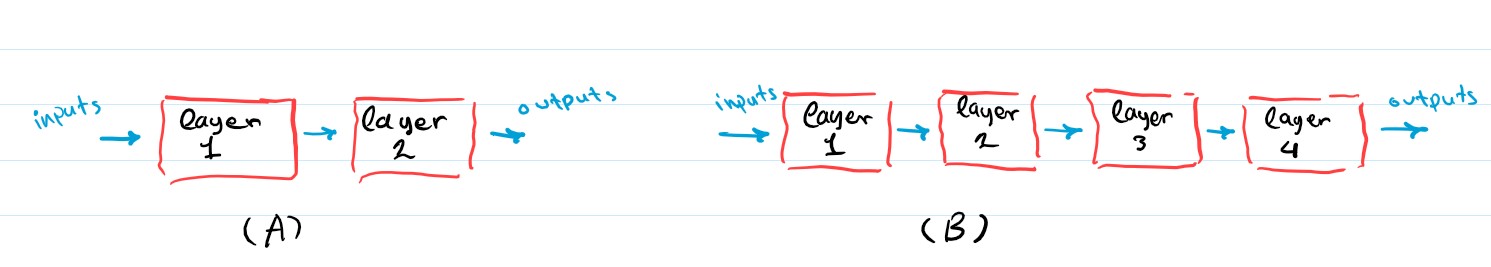

Something like this happens

The obvious question now rises, adding more layers means a better network right? well..

At least, it is not as straightforward as you would expect. It was empirically proven that adding more layers usually results in a better performing network, a common problem however arises when you start adding tens of layers, called vanishing/exploding gradients, this problem can prevent the network from learning properly, but it has been mitigated using normalized weights initializations and normalization layers.

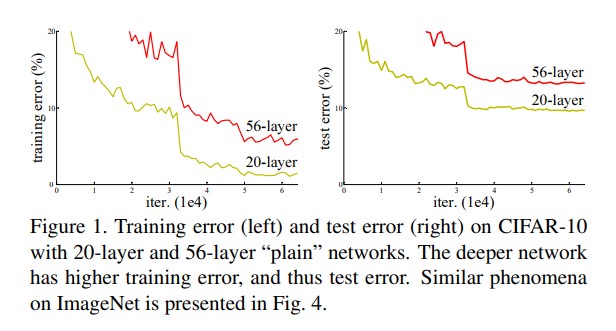

Still, naively adding even more layers results in networks that performed worse than their shallow counterparts on both the training and test set, which means this was NOT an overfitting problem, as shown in the following figure from the original paper.

So, maybe adding more layers to a neural network just makes these networks perform worse and that’s it, we should avoid constructing very deep neural networks, right?

Well, No. This result IS counter-intuitive, a network with more layers should at least in theory perform as well as its shallow counterpart. Consider two networks, a shallow network (A) and a deeper version network (B).

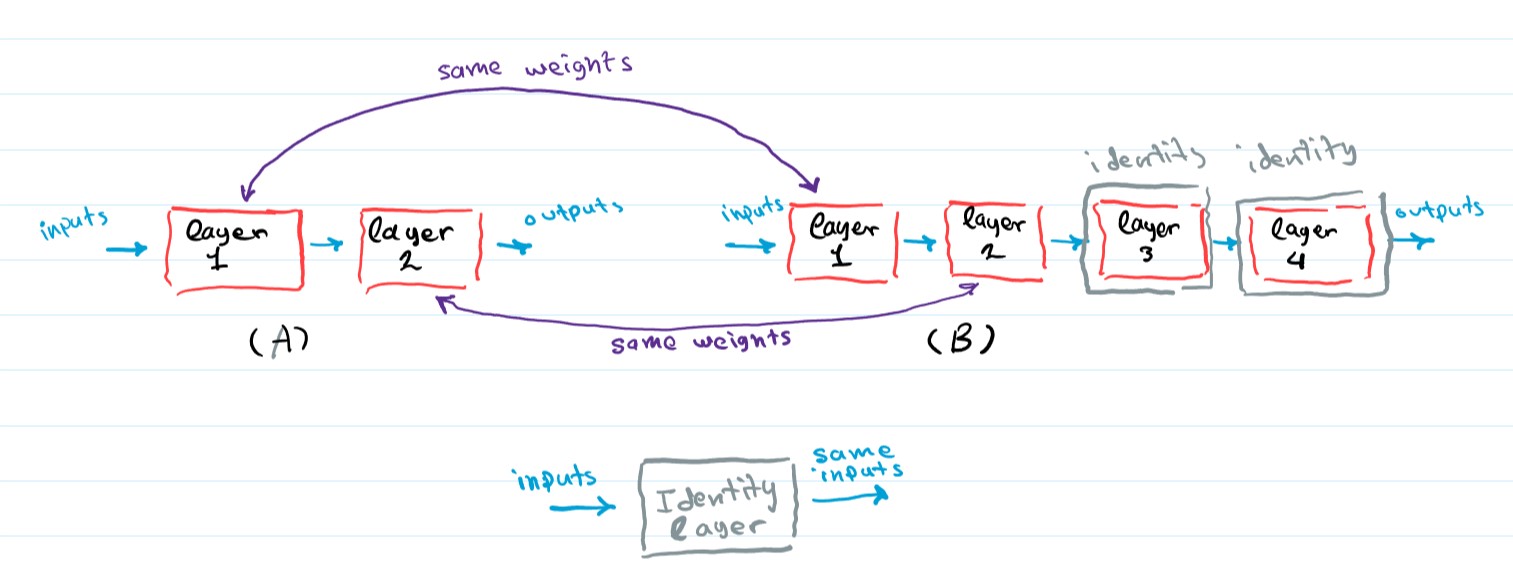

Now assuming network (A) is trained on some random task, network (B) can always mimic network (A)’s performance by copying the first two layers weights and turning layers 3 and 4 into Identity layers, layers that only forward its inputs (layer(x) = x), as shown.

In other words, the larger network should be able to optimize its weights in a way that it can at least match the shallower network performance if it can’t beat it. In practice though the network struggles to optimize its weights that way. The paper suggests that the current optimization techniques struggle to find a solution even close to the shallow + identity layers one. This suggests that not all networks are as easy to optimize.

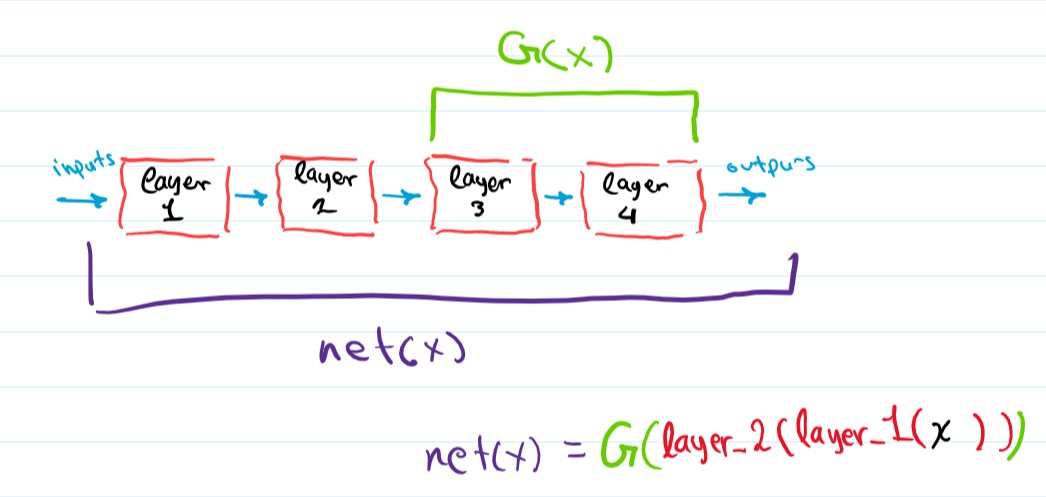

Now before going into the solution the paper propsed. I’d like to point out one other way to view neural nets that can be helpful. Neural networks can be viewed as mathematical functions, they are basically a composotion of several functions, these several functions that compose the network are the network’s layers. For example, let net(x) be a neural network with three layers, then net(x) is basically layer_3(layer_2(layer_1(x))), a number a consecutive layers can also be considered a function (this will be useful), we can for example combine layers 2 and 3 and in one function G(x) := layer_3(layer_2(x)), and represent net as G(layer_1(x)).

I should note that when I say net(x), I actually mean net(x, W), where W is the network’s weights, this also goes with layer_1(x, W), G(x, W), where each W refers to the layer or layers weights, but to simplify the notation I’ll forbid the Ws.

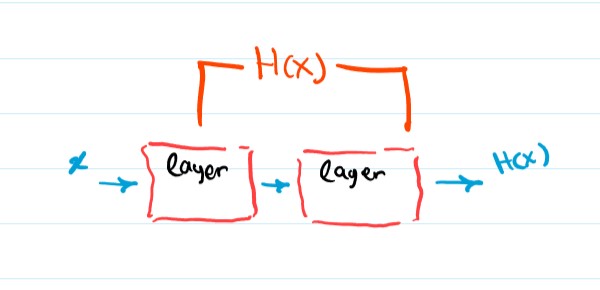

Now back to our problem, how do we optimize a very deep neural network? We can view a few consecutive layers as trying to fit an underlying function that we will call H(x), these layers are trying to optimize their weights in a way that makes them identitcal to H(x), ideally H(x) is a mapping that transforms the inputs into a more useful representation, or at least forwards the inputs (identity function) if you can’t get better than what is already there.

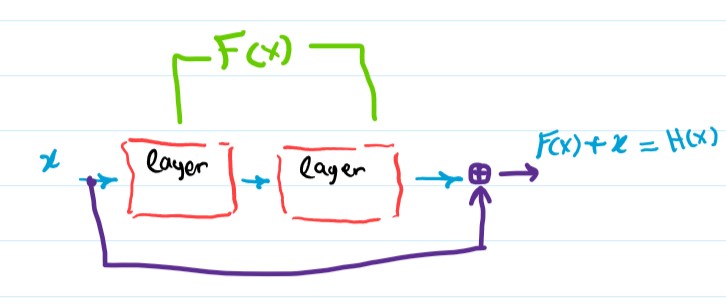

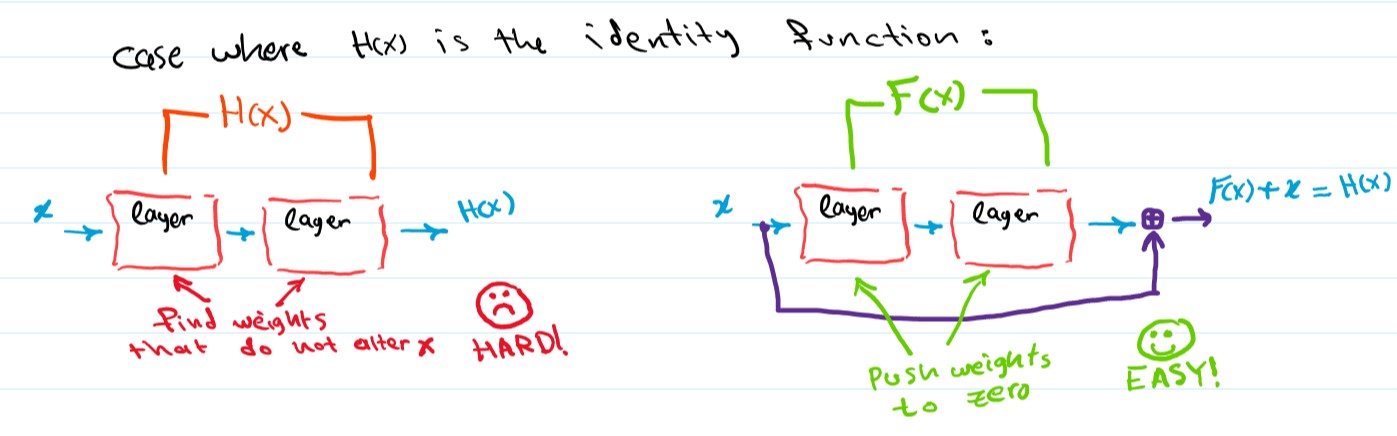

The paper argues that learning H(x) directly is not easy, instead we can let the consecutive layers learn a different mapping that we call F(x), where F(x) := H(x) - x, this way H(x) = F(x) + x. We are still learning H(x) but in a different way that the paper suggests is easier.

To see how the new formulation might be easier to optimize, consider the case where the Identity function is the optimal solution i.e. the underlying mapping H(x) is the identity function, the new formulation (letting the layers learn the mapping F(x)) will just push the weights of the layers to zero therefore F(x) = 0, and H(x) = F(x) + x will become H(x) = x, the identity function. Trying to learn the Identity function through the original approach (direcly learning H(x)) is harder, the layers will have to optimize their weights in a way that does nothing to the inputs, which is not as easy as just pushing the weights to zeros.

The new formulation also preconditions the layers in a way that makes them closer to an identity mapping rather than a zero mapping (weights are normally initialized with values near 0 which makes layers act like zero mappings), the paper emperically shows that this preconditioning seems reasonable since the optimal underlying mapping is generally not the identity function but a function close to it (that’s why starting from an identity mapping is a good preconditioning).

This simple reformulation allows us to train very deep neural networks, and has been used in different architectures across deep learning. The networks that first utilized this trick were called “Resnet”.